ADHD coexisting with SLD

Co-morbidities with SLD Understanding SLD

By Dr. Venkateshwaran MBBS MD (psychiatry), post doctoral fellowship in Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (CMC, Vellore)

ADHD coexisting with SLD

Specific Learning Disorder (SLD) is an important cause of scholastic backwardness. Review of 17 Indian studies (by Kuriyan and James 2000 to 2017) found the mean prevalence of SLD as 10%.

ADHD is another neurodevelopmental disorder which significantly causes significant long term psychological morbidity.

Clinical presentation of ADHD:

Symptoms of ADHD include hyperactivity, inattention and impulsivity. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder usually manifests in early or middle childhood. In many cases, hyperactivity symptoms predominate in preschool and decrease with age, such that they are no longer prominent beyond adolescence or may instead be reported as feelings of physical restlessness. Attentional problems may be more commonly observed beginning in later childhood, especially in school and among adults in occupational settings.

The manifestations and severity of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder often vary according to the characteristics and demands of the environment. Symptoms and behaviors should be evaluated across multiple types of environments as a part of clinical assessment. Where available, teacher and parent reports should be obtained to establish the diagnosis in children and adolescents. In adults, the report of a significant other, family member or co-worker can provide important additional information. (clinical psychologist, psychiatrist or special educators should not exclude ADHD based only on their one-to-one interaction during assessment process).

In a subset of individuals with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, especially in children, an exclusively inattentive presentation may occur. There is no hyperactivity, and the presentation is characterized by daydreaming, mind-wandering and a lack of focus. These children are sometimes referred to as exhibiting a “restrictive inattentive pattern of symptoms” or “sluggish cognitive tempo”.

Symptoms of inattention include:

- Inattention: having difficulty sustaining attention on tasks that do not provide a high level of stimulation or reward or require sustained mental effort; lacking attention to detail; making careless mistakes in school or work assignments; not completing tasks.

- Distraction: being easily distracted by extraneous stimuli or thoughts not related to the task at hand; often seeming not to listen when spoken to directly; frequently appearing to be daydreaming or to have their mind elsewhere.

- Executive dysfunctions: Losing things; being forgetful in daily activities; having difficulty remembering to complete upcoming daily tasks or activities; having difficulty planning, managing and organizing schoolwork, tasks and other activities.

Inattention may not be evident when the individual is engaged in activities that provide intense stimulation and frequent rewards.

In a subset of individuals with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, combined presentation, severe inattentiveness and hyperactivity-impulsivity are both consistently present in most of the situations that an individual encounters and are also evidenced by the clinician’s own observations. This pattern is often referred to as “hyperkinetic disorder” and is considered a more severe form of the disorder.

Symptoms include

- Hyperactivity:

- Children showing excessive motor activity; leaving their seat when expected to sit still; often running about;

- Children having difficulty sitting still without fidgeting (younger children); displaying feelings of physical restlessness and a sense of discomfort with being quiet or sitting still (adolescents and adults);

- Children having difficulty engaging in activities quietly; talking too much

- Impulsivity:

- Children blurting out answers in school or comments at work; having difficulty waiting their turn in conversation, games or activities; interrupting or intruding on others’ conversations or games.

- Children having a tendency to act in response to immediate stimuli without deliberation or consideration of risks and consequences (e.g. engaging in behaviors with potential for physical injury; impulsive decisions; reckless driving).

- Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder symptoms often significantly limit academic achievement. ADHD has higher risk of long term psychological morbidity including substance abuse, trauma, violence.

Impact of ADHD in SLD:

Around 25% of children with SLD have a comorbid attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), which impacts progress in remediation implemented in SLD. Studies have compared children having SLD with comorbid ADHD and found that children with ADHD are more impaired than SLD in cognitive inhibition, cognitive flexibility, verbal memory, working memory, and intellectual functioning. They are also impaired in processing speed, planning and organization which are important skills sets for academic achievement.

Management of ADHD:

Assessment:

To make a diagnosis of ADHD clinicians should conduct a clinical interview with parents, examine and observe the child, and obtain information from parents and teachers through DSM V/ICD 11 based ADHD rating scales. Normative data are available for the DSM-5–based rating scales for ages 5 years to the 18th birthday.

Treatment:

Pre-school children: (4-6 years)

Clinicians should prescribe evidence-based parent trained behavioral management (PTBM) and/or behavioral classroom interventions as the first line of treatment, if available (grade A: strong recommendation).

Methylphenidate may be considered if these behavioral interventions do not provide significant improvement and there is moderate-to-severe continued disturbance in the 4- through 5-year-old child’s functioning.

In areas in which evidence-based behavioral treatments are not available, the clinician needs to weigh the risks of starting medication before the age of 6 years against the harm of delaying treatment.

School aged children:

For elementary and middle school–aged children (age 6 years to the 12th birthday) with ADHD, clinician are recommended to use approved medications for ADHD, along with PTBM and/or behavioral classroom intervention (preferably both PTBM and behavioral classroom interventions).

Educational interventions and individualized instructional supports, including school environment, class placement, instructional placement, and behavioral supports, are a necessary part of any treatment plan and often include an Individualized Education Program (IEP) or a rehabilitation plan.

Adolescents:

For adolescents (12 – 18 years) with ADHD, clinicians are recommended to use approved medications for ADHD with the adolescent’s assent (grade A: strong recommendation). They are encouraged to prescribe evidence-based training interventions and/or behavioral interventions as treatment of ADHD, if available.

Status of sensory integration in ADHD:

American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) policy statement, 2012 do not recommend routine use of sensory integration therapies in ADHD

Clinicians should communicate with families about the limited data on the use of sensory-based therapies for children with ADHD.

If therapist is using sensory-based therapies, the clinician can play an important role in teaching families how to determine whether a therapy is effective.

Help families design simple ways to monitor effects of treatment (eg, behavior diaries, pre-post behavior rating scales). Help the family be specific and create explicit treatment goals, designed at the onset of therapy, focused on improving the individual’s ability to engage and participate in everyday activities.

Set a time limit for seeing the family back to discuss whether the therapy is working to achieve the stated goals.

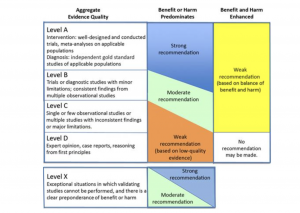

Fig 1: Levels of evidence: